肝星状细胞通过胱硫醚γ-裂解酶/硫化氢(CSE/H2S)调控肝细胞癌细胞凋亡的作用及其机制

DOI: 10.12449/JCH241117

Role and mechanism of hepatic stellate cells in regulating the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through cystathionine γ-lyase/hydrogen sulfide

-

摘要:

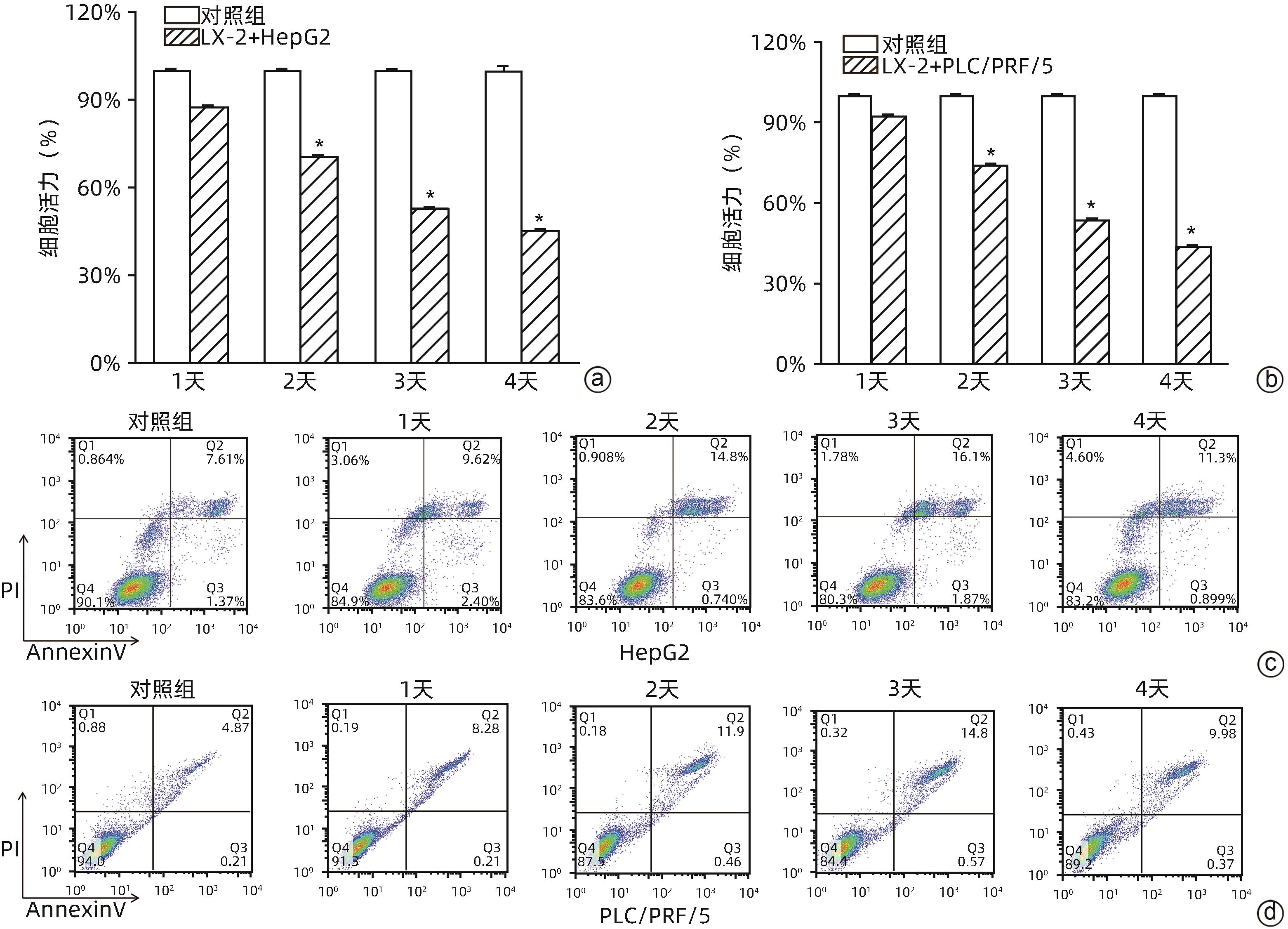

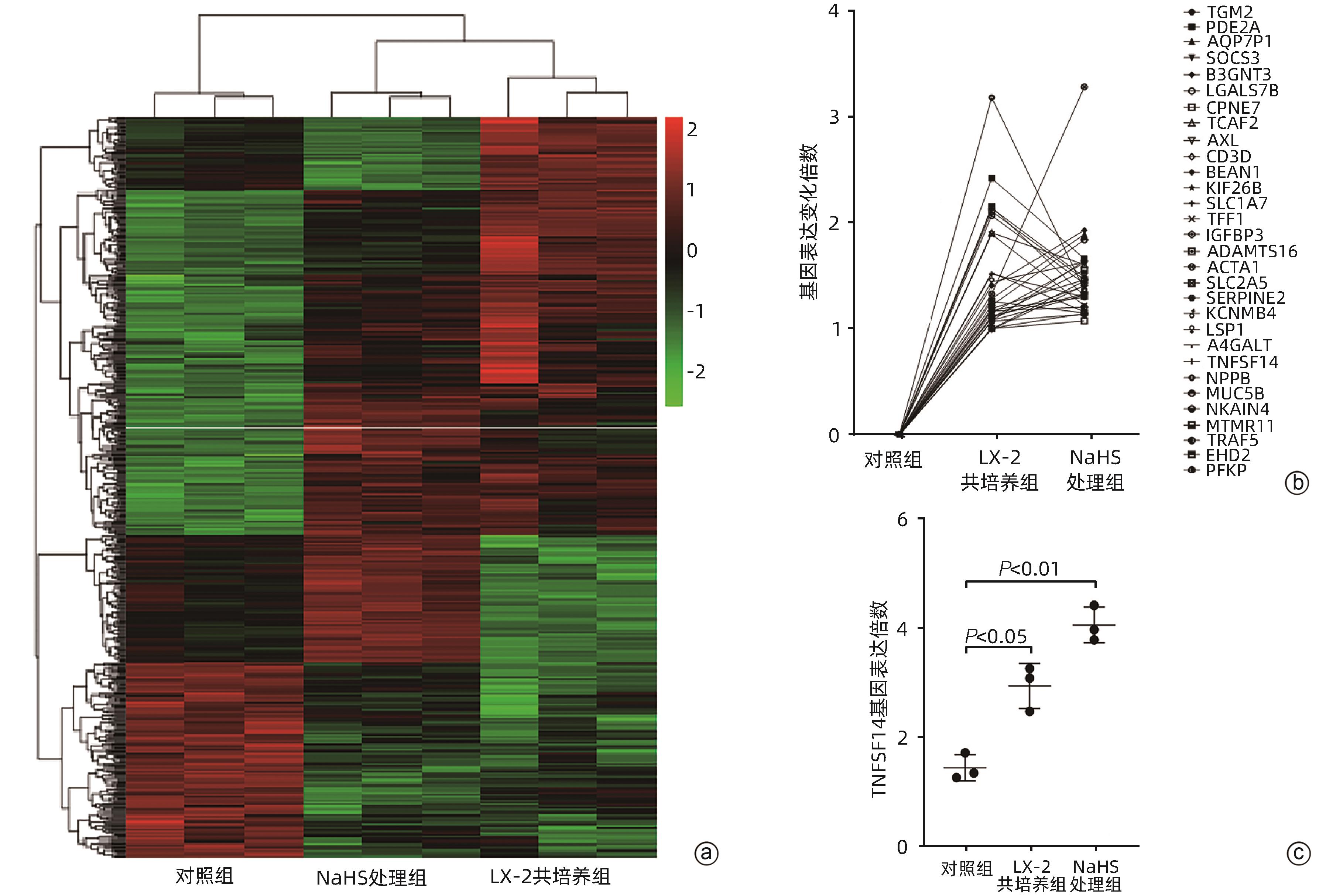

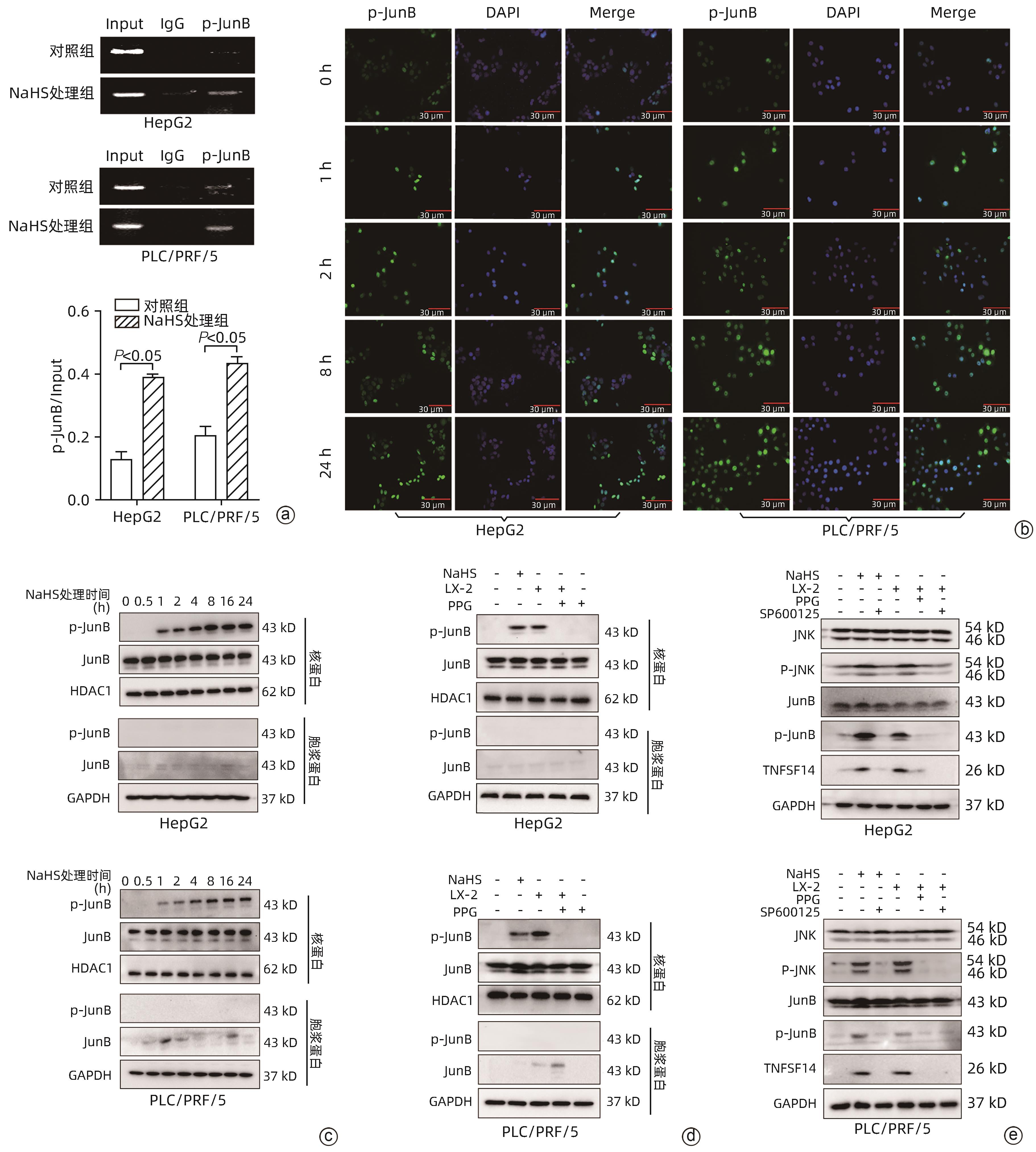

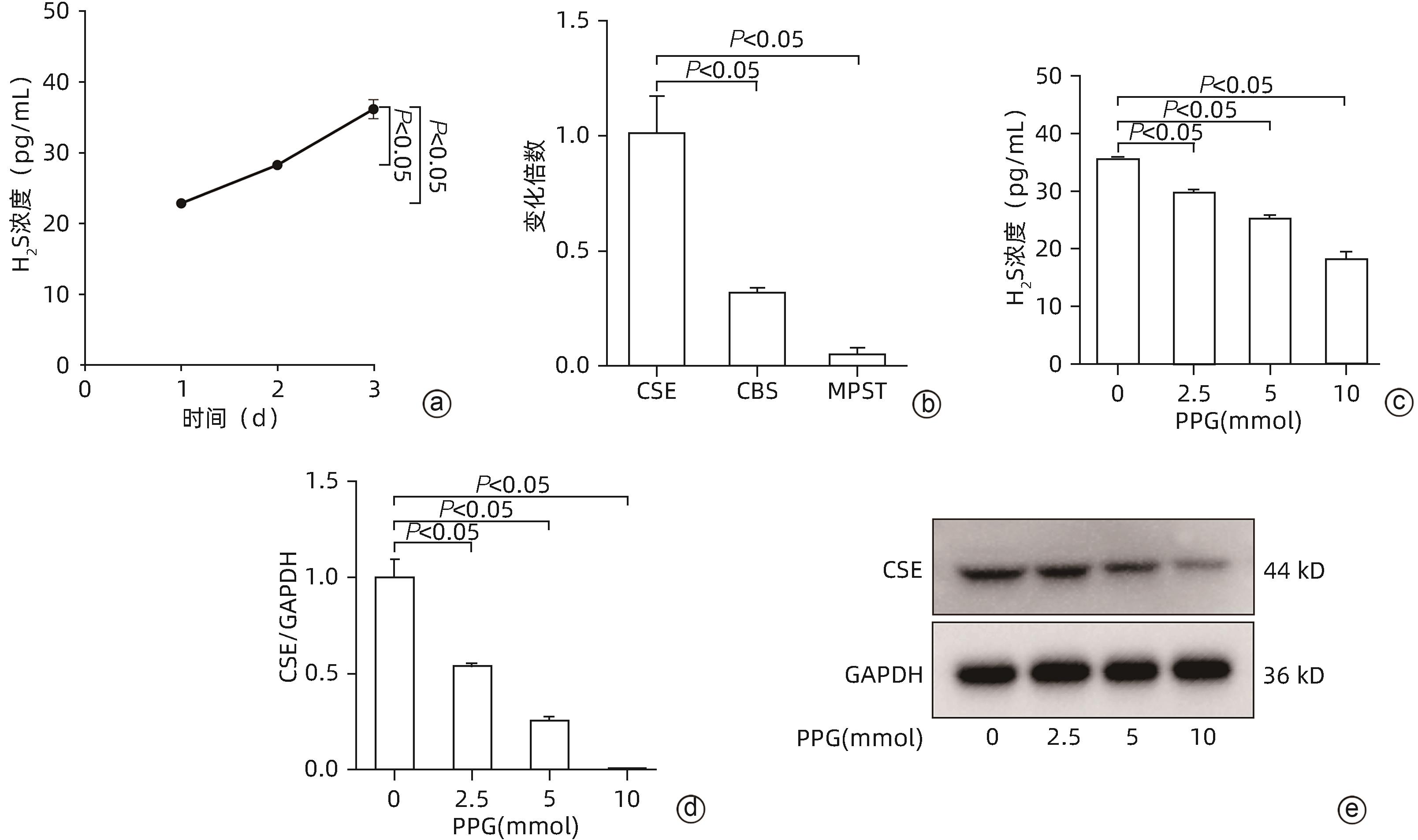

目的 肝星状细胞(HSC)和硫化氢(H2S)信号分子作为肝细胞癌(HCC)微环境中重要的组分,参与调控HCC的发生发展等多种生物学进程。本研究通过HSC与肝癌细胞系共培养,探讨HSC通过分泌H2S参与调控肝癌细胞凋亡的作用及其机制。 方法 以HSC细胞系(LX-2)及肝癌细胞系(HepG2、PLC/PRF/5)为研究对象。RT-qPCR和Western Blot(WB)法检测LX-2中H2S关键合成酶——胱硫醚γ-裂解酶(CSE)mRNA及表达水平;ELISA测定上清液LX-2产生的H2S浓度;二代测序、细胞免疫荧光、染色质免疫沉淀(ChIP)及WB检测H2S(内源性和外源性)作用HepG2和PLC/PRF/5细胞后,JNK/JunB-TNFSF14信号通路基因、结合位点及相关蛋白。Transwell小室将LX-2分别与HepG2和PLC/PRF/5共培养,CCK-8和流式细胞术检测肝癌细胞的细胞活力、凋亡,WB测定H2S-TNFSF14信号通路相关蛋白。所有细胞实验均重复3次。计量资料两组间比较采用成组t检验;多组间比较采用单因素方差分析或重复测量方差分析,进一步两两比较采用Dunnett-t检验。 结果 LX-2主要通过CSE合成H2S,LX-2培养上清液中H2S浓度随着时间延长逐渐增加[(22.89±0.08)pg/mL vs (28.29±0.15)pg/mL vs (36.19±1.90)pg/mL,F=79.63,P<0.05]。LX-2中CSE mRNA水平显著高于CBS mRNA和MPST mRNA(1.008±0.13 vs 0.320±0.014 vs 0.05±0.02, F=80.84,P<0.05)。当CSE被炔丙基甘氨酸(PPG)抑制之后,随着PPG浓度增加,H2S浓度下降(P<0.05)。LX-2分别与HepG2、PLC/PRF/5共培养,随着培养时间延长,HepG2(87.48%±0.82% vs 70.48%±0.641% vs 52.89%±0.57% vs 45.20%±0.69%, F=1 517.13,P<0.001)和PLC/PRF/5(92.41%±0.48% vs 74.10%± 0.73% vs 53.70%±0.60% vs 44.00%± 0.27%,F=2 626.21,P<0.001)细胞活力降低;凋亡增加(HepG2:12.88%±0.64% vs 15.5%±0.16% vs 18.43%±0.37% vs 13.01%±0.58%,F=142.15,P<0.001;PLC/PRF/5:8.51±0.05 vs 12.80±0.33 vs 15.59±0.21 vs 10.72±0.30,F=676.40,P<0.001),第3天最显著。二代测序显示,内源性H2S(LX-2产生)和NaHS(外源性H2S供体)参与调控HepG2中多种基因表达。NaHS和LX-2通过释放H2S,激活肝癌细胞中JNK/JunB信号通路、上调凋亡基因TNFSF14表达,且p-JunB与TNFSF14基因转录调控区域结合增加。 结论 在肝癌微环境中,HSC通过信号分子CSE/H2S,激活了肝癌细胞中JNK/JunB信号通路,TNFSF14表达增加,从而促进了肝癌细胞凋亡。 Abstract:Objective As important components in the microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) participate in various biological processes that regulate the development and progression of HCC. Through the co-culture of HSCs and HCC cells, this article aims to investigate the role and mechanism of HSCs in regulating the apoptosis of HCC cells by secreting H2S. Methods The HSC cell line (LX-2) and HCC cell lines (HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5) were used for experiment. RT-qPCR and Western Blot (WB) were used to measure the mRNA and protein expression levels of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), a key synthase for H2S; ELISA was used to measure the concentration of H2S in supernatant; next-generation sequencing, cell immunofluorescence assay, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and WB were used to measure the JNK/JunB-TNFSF14 signaling pathway genes, binding sites, and related proteins after HepG2 cells were treated by H2S. LX-2 cells were co-cultured with HepG2 or PLC/PRF/5 cells in a Transwell chamber; CCK-8 assay and flow cytometry were used to measure the viability and apoptosis of HCC cells, and WB was used to measure the H2S-TNFSF14 signaling pathway-related proteins. All cell experiments were repeated three times. The independent-samples t test was used for comparison of continuous data between two groups; a one-way analysis of variance or the analysis of variance with repeated measures was used for comparison between multiple groups, and the Dunnett-t test was used for further comparison between two groups. Results LX-2 cells synthesized H2S mainly through CSE, and the concentration of H2S in supernatant of LX-2 cells gradually increased over time (22.89±0.08 pg/mL vs 28.29±0.15 pg/mL vs 36.19±1.90 pg/mL, F=79.63, P<0.05). In LX-2 cells, the mRNA expression level of CSE was significantly higher than that of CBS and MPST (1.008±0.13 vs 0.320±0.014 vs 0.05±0.02, F=80.84, P<0.05). When CSE was inhibited by PPG, the concentration of H2S decreased with the increase in the concentration of PPG (P<0.05). LX-2 cells were co-cultured with HepG2 or PLC/PRF/5 cells, and over the time of culture, there were significant reductions in the viability of HepG2 cells (87.48%±0.82% vs 70.48%±0.641% vs 52.89%±0.57% vs 45.20%±0.69%, F=1 517.13, P<0.001) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (92.41%±0.48% vs 74.10%±0.73% vs 53.70%±0.60% vs 44.00%±0.27%, F=2626.21, P<0.001) and significant increases in the apoptosis of HepG2 cells (12.88%±0.64% vs 15.5%±0.16% vs 18.43%±0.37% vs 13.01%±0.58%, F=142.15, P<0.001) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (8.51±0.05 vs 12.80±0.33 vs 15.59±0.21 vs 10.72±0.30, F=676.40, P<0.001), with the most significant changes on day 3. Next-generation sequencing showed that endogenous H2S and NaHS (endogenous H2S donor) were involved in regulating the expression of various genes in HepG2 cells. By releasing H2S, NaHS and LX2 activated the JNK/JunB signaling pathway and upregulated the expression of the apoptosis gene TNFSF14 in HCC cells, with increased binding between p-JunB and the transcriptional regulatory regions of the TNFSF14 gene. Conclusion In the microenvironment of HCC, HSCs activate the JNK/JunB signaling pathway in HCC cells through the signal molecules CSE/H2S, and there is an increase in the expression of TNFSF14, thereby promoting the apoptosis of HCC cells. -

Key words:

- Carcinoma, Hepatocellular /

- Hepatic Stellate Cells /

- Hydrogen Sulfide

-

注: a,ChIP显示,在HepG2和PLC/PRF/5细胞中,p-JunB与TNFSF14启动子结合力增加;b,NaHS分别处理HepG2和PLC/PRF/5 0、1、2、8、24 h后,HepG2和PLC/PRF/5细胞核中p-JunB表达及核转位,DAPI(蓝色)和FITC(绿色)分别为对细胞核DNA及p-JunB进行染色;c,NaHS不同处理时间后,HepG2和PLC/PRF/5细胞核与细胞质中p-JunB的表达;d,NaHS处理组和LX-2共培养组HepG2及PLC/PRF/5细胞的p-JunB蛋白变化;e,PPG和SP600125抑制了H2S及NaHS对HepG2与PLC/PRF/5中JNK/p-JNK、JunB/p-JunB、TNFSF14蛋白水平。

图 4 内源性H2S和NaHS通过激活JNK/JunB信号通路调控TNFSF14转录

Figure 4. Endogenous H2S and NaHS upregulated TNFSF14 via JNK/JunB signaling pathway

表 1 RT-qPCR和ChIP-PCR所需要的引物序列

Table 1. Primers for Real-Time PCR and ChIP-PCR

项目 寡核苷酸序列 RT-qPCR引物 TNFSF14 F:5'-CGTGAGACCTTCGCTCTTGTAT-3' R:5'-CCCTCAGTGTTTGTGGTGGAT-3' CSE F:5'-AAGACGCCTCCTCACAAGGT-3' R:5'-ATATTCAAAACCCGAGTGCTGG-3' GAPDH F:5'-TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGA-3' R:5'-CCTGGAAGATGGTGATGGGAT-3' CBS F:5'-AATGGTGACGCTTGGGAA-3'

R:5'-TGAGGCGGATCTGTTTGA-3'

MPST F:5'-GACCCCGCCTTCATCAAG-3'

R:5'-CATGTACCACTCCACCCA-3'

ChIP-qPCR引物 TNFSF14 F:5'-TTGTTCATTGCTGCATCCCC-3' R:5'-CTCCTCTTCTTCCGGTACCC-3' -

[1] MYOJIN Y, HIKITA H, SUGIYAMA M, et al. Hepatic stellate cells in hepatocellular carcinoma promote tumor growth via growth differentiation factor 15 production[J]. Gastroenterology, 2021, 160( 5): 1741- 1754. e 16. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.015. [2] MA YN, WANG SS, LIEBE R, et al. Crosstalk between hepatic stellate cells and tumor cells in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Chin Med J, 2021, 134( 21): 2544- 2546. DOI: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001726. [3] SUFLEŢEL RT, MELINCOVICI CS, GHEBAN BA, et al. Hepatic stellate cells-from past till present: Morphology, human markers, human cell lines, behavior in normal and liver pathology[J]. Rev Roum De Morphol Embryol, 2020, 61( 3): 615- 642. DOI: 10.47162/RJME.61.3.01. [4] LIN N, CHEN ZJ, LU Y, et al. Role of activated hepatic stellate cells in proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatol Res, 2015, 45( 3): 326- 336. DOI: 10.1111/hepr.12356. [5] GENG ZM, LI QH, LI WZ, et al. Activated human hepatic stellate cells promote growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma in a subcutaneous xenograft nude mouse model[J]. Cell Biochem Biophys, 2014, 70( 1): 337- 347. DOI: 10.1007/s12013-014-9918-3. [6] YANG HX, TAN MJ, GAO ZQ, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide and hypoxia in hepatic angiogenesis of portal hypertension[J]. J Clin Transl Hepatol, 2023, 11( 3): 675- 681. DOI: 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00217. [7] LIU Y, XUN ZZ, MA K, et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2023, 78( 4): 770- 782. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.011. [8] SHACKELFORD R, OZLUK E, ISLAM MZ, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and DNA repair[J]. Redox Biol, 2021, 38: 101675. DOI: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101675. [9] ANDRÉS CMC, PÉREZ DE LA LASTRA JM, ANDRÉS JUAN C, et al. Chemistry of hydrogen sulfide-pathological and physiological functions in mammalian cells[J]. Cells, 2023, 12( 23): 2684. DOI: 10.3390/cells12232684. [10] WANG SS, CHEN YH, CHEN N, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes autophagy of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2017, 8( 3): e2688. DOI: 10.1038/cddis.2017.18. [11] ZHANG CH, JIANG ZL, MENG Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide and its donors: Novel antitumor and antimetastatic agents for liver cancer[J]. Cell Signal, 2023, 106: 110628. DOI: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110628. [12] YUAN ZN, ZHENG YQ, WANG BH. Prodrugs of hydrogen sulfide and related sulfur species: Recent development[J]. Chin J Nat Med, 2020, 18( 4): 296- 307. DOI: 10.1016/S1875-5364(20)30037-6. [13] YOUNESS RA, HABASHY DA, KHATER N, et al. Role of hydrogen sulfide in oncological and non-oncological disorders and its regulation by non-coding RNAs: A comprehensive review[J]. Noncoding RNA, 2024, 10( 1): 7. DOI: 10.3390/ncrna10010007. [14] GAO W, LIU YF, ZHANG YX, et al. The potential role of hydrogen sulfide in cancer cell apoptosis[J]. Cell Death Discov, 2024, 10( 1): 114. DOI: 10.1038/s41420-024-01868-w. [15] HAN B, WU LQ, MA X, et al. Synergistic effect of IFN-γ gene on LIGHT-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells via down regulation of Bcl-2[J]. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol, 2011, 39( 4): 228- 238. DOI: 10.3109/10731199.2010.538403. [16] ZHENG QY, CAO ZH, HU XB, et al. LIGHT/IFN-γ triggers β cells apoptosis via NF-κB/Bcl2-dependent mitochondrial pathway[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2016, 20( 10): 1861- 1871. DOI: 10.1111/jcmm.12876. [17] ZHANG N, LIU XH, QIN JL, et al. LIGHT/TNFSF14 promotes CAR-T cell trafficking and cytotoxicity through reversing immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment[J]. Mol Ther, 2023, 31( 9): 2575- 2590. DOI: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.06.015. [18] SKEATE JG, OTSMAA ME, PRINS R, et al. TNFSF14: LIGHTing the way for effective cancer immunotherapy[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 922. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00922. [19] SHAULIAN E, KARIN M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2002, 4( 5): E131- E136. DOI: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [20] YAN P, ZHOU B, MA YD, et al. Tracking the important role of JUNB in hepatocellular carcinoma by single-cell sequencing analysis[J]. Oncol Lett, 2020, 19( 2): 1478- 1486. DOI: 10.3892/ol.2019.11235. -

PDF下载 ( 3446 KB)

PDF下载 ( 3446 KB)

下载:

下载: